New ASU center to help make better water decisions faster

Arizona’s water supply — including the Colorado River, which also provides water to six other Western states — is drying up. A warming climate is causing the region to undergo aridification, a process of permanently increasing dryness that goes beyond temporary drought conditions. Demand for water continues to grow, particularly in agriculture, despite the dwindling supply.

When rain does come to this parched region, it’s not all good news. Climate change is intensifying extreme weather events such as the atmospheric rivers that recently hit California, leading to devastating flooding and additional challenges to retaining the influx of water to refill reservoirs.

To keep this vital resource flowing now and in the future, decision-makers at both the local and national levels need the right information to make plans and policies related to water.

They rely in part on academic experts in hydrology, which is the study of water and its movement and relationship with the environment on and below the Earth’s surface, to provide critical data that can inform policy decisions.

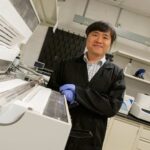

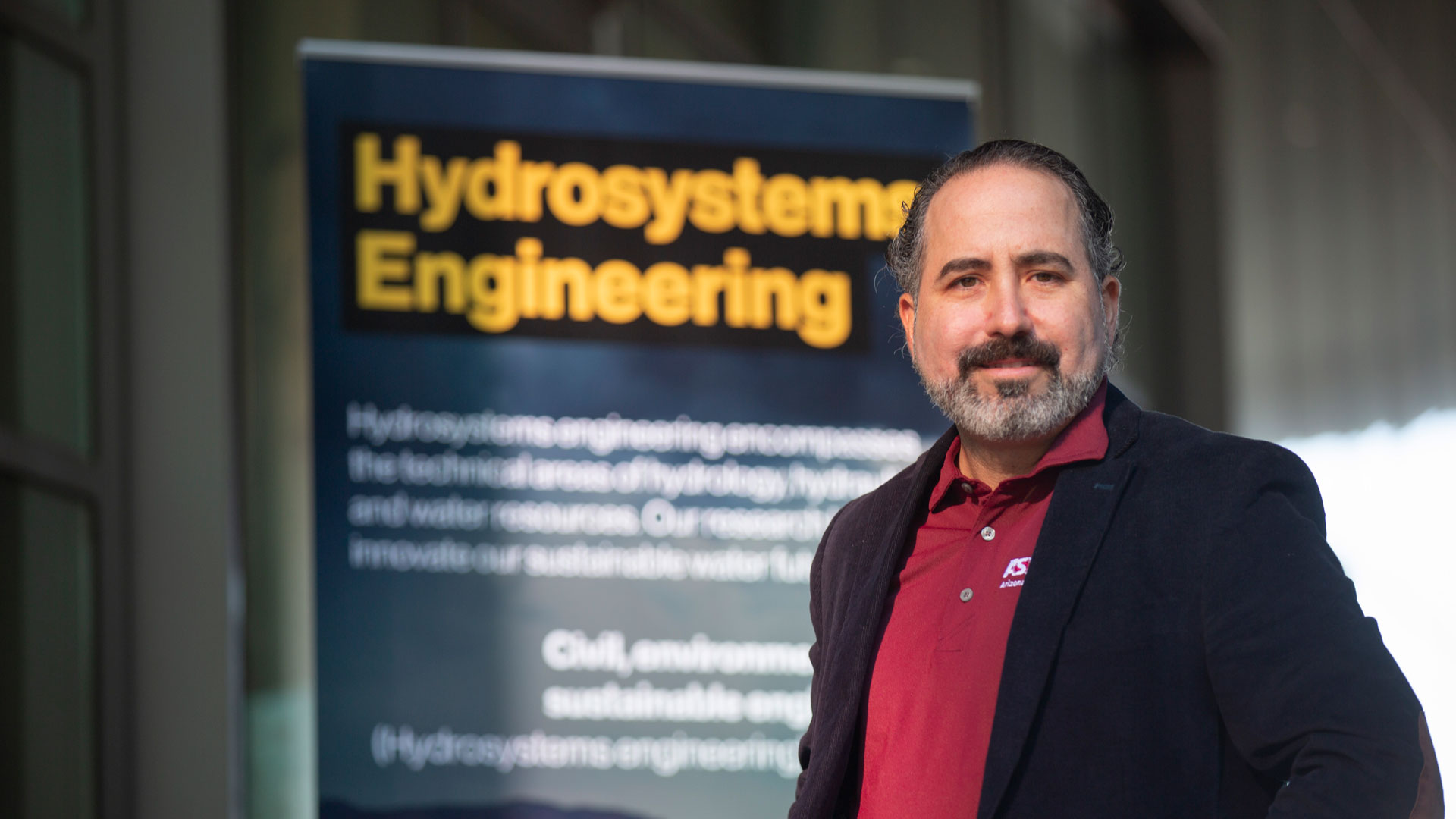

“Whether there’s too much or too little water impacts the entire range of societal institutions, from municipal governments to multinational corporations,” says Enrique Vivoni, the Fulton Professor of Hydrosystems Engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University. “Better decision-making requires better information from the past, present and future. Using leading-edge technologies that provide sensing, prediction and analysis capabilities, water resources management can be enhanced for public benefit.”

To use this information and technology effectively, the research community and water management stakeholders need to work together. So, Vivoni is leading efforts to more quickly translate academic expertise and research into actionable tools for decision-makers in a new research center.

The Center for Hydrologic Innovations — a partnership between the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, part of the Fulton Schools, and the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory — brings together academic researchers and external stakeholders to collaboratively develop solutions that can address the most pressing water challenges in the desert southwest.

The center provides support to other centers and initiatives at the university and builds on ASU’s strengths in water science and resource management, which were recently recognized through the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative, a $40 million investment by the state of Arizona. ASU was chosen to lead this multiyear initiative to provide immediate, actionable and evidence-based solutions to help ensure Arizona will continue to thrive with a secure future water supply.

The center exemplifies ASU’s charter and mission to advance research of public value and serve the community. It is also well positioned to make positive economic and environmental impacts in Arizona and beyond by drawing on the university’s strengths in entrepreneurship and technology transfer with support from Skysong Innovations and a focus on workforce development in line with the New Economy Initiative.

“Through applied engineering projects, the folks we’re working with and working for have a say in the development of products that they can immediately use,” says Vivoni, the center’s director and a senior global futures scientist with the ASU Global Futures Laboratory.

Enrique Vivoni is the director of the Center for Hydrologic Innovations. He says collaboration between hydrosystems engineering researchers and other organizations involved in water management decisions is the way forward to solving the region’s water challenges. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

A collaborative approach to research

The center’s activities are structured in what Vivoni calls “solution spaces.” In each solution space, faculty and student researchers collaborate with partners in utilities, government agencies, industry or other groups. These partners come together through a shared interest in a specific water management issue, such as water resilience and sustainability, climate and hydrologic hazards, or natural resource management.

From the start of a project in a given solution space, all partners involved work together to define a research question and develop a tool that is impactful and immediately applicable to a real-world issue.

“It’s a fairly new way of doing work in engineering,” says Vivoni, noting that academic research in hydrosystems engineering and water management research has often been disconnected from and out of reach for the stakeholders who could use it.

Each partner brings expertise the others need for designing effective solutions. The faculty researchers combine expertise in Earth-observing systems, numerical prediction systems, big data analytics and other advances in scientific knowledge to develop new tools.

Government, industry and other partners offer valuable perspective and feedback on how the tools can be implemented, how they fit within the regulatory space and provide additional data for researchers to use in their models and visualization platforms.

“Through this process of continual feedback, we get to a final product in which the stakeholders and others involved in the partnerships have made key decisions along the way,” Vivoni says. “Folks at agencies and utilities have been very appreciative of this because we’re opening the ‘black box’ of the research process.”

Margaret Garcia, an assistant professor of hydrosystems engineering and researcher in the center, believes solution spaces will improve her and her colleagues’ ability to make an impact on water management policy.

“Understanding stakeholder perspectives and needs and fostering trust is key to having our research be ultimately used in policymaking and design and operational decisions,” she says. “I think the solution spaces approach of pairing stakeholder partners and research problems at the project conceptualization phase will increase the probability and pace of successful technology transfer.”

Expanding hydrosystems engineering research impact

Vivoni has demonstrated this method’s efficacy in his own hydrosystems engineering research over the past several years.

Three of Vivoni’s collaborations have contributed to early projects of the center. One involved exploring the benefits of wildfire prevention treatments on water supply for the Salt River Project. Another focused on developing a web-based tool with the Central Arizona Project to assess short-term and long-term climate scenarios and their impact on the Colorado River. In the third project he worked with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to enhance observation of arid rivers in the Western U.S. to determine when water is present, assess when flooding is likely and develop effective streamflow management techniques.

Through the Center for Hydrologic Innovations, he hopes to expand this approach to help his colleagues in the hydrosystems engineering domain at ASU increase their impact critical areas of need: hydrologic modeling, remote sensing of water applications, big data analytics, water sustainability, hydrologic impact assessments and similar topics.

The group of seven faculty members — Vivoni and Garcia along with Assistant Professors Tianfang Xu, Ruijie Zeng, Saurav Kumar and Rebecca Muenich and Associate Professor Giuseppe Mascaro — are a dynamic group of researchers who are establishing themselves as reputed scholars in the field. Vivoni hopes that, with the center in place, he can fast-track the career growth of younger scholars and faculty colleagues.

“We’re creating opportunities for faculty researchers and their students to grow, to contribute to something bigger than any individual effort, get their work out there and connect with others in ways that would normally take 15 or 20 years to achieve,” Vivoni says. “I’m trying to short-circuit the length of time that it took me to reach this particular stage.”

So far, they’ve worked together closely to develop the hydrosystems engineering curriculum in the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, Garcia says. However, this is their first foray to coordinate research efforts.

“I believe that the Center for Hydrologic Innovations will facilitate the collaboration needed to tackle the broad and complex water challenges we face,” Garcia says.

Together with other colleagues at ASU, they have collaborated on developing the center’s strategies, goals and potential partners.

The team of faculty researchers is also beginning work on their own projects through the center’s solution spaces, including a nature-based water management effort led by Muenich with funding and partnership from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Mascaro is leading another project in collaboration with Xu and colleagues from the University of Arizona, Northern Arizona University and the Arizona Department of Water Resources. As a group, they will identify opportunities to capture water that would normally evaporate to store it underground without affecting surface water flows. The team will also assess the potential of this method to increase Arizona’s water supply.

“[The center’s model] is a great way of readily transferring our research outcomes into practice,” Mascaro says. “The interaction with stakeholders is not new to me since I have done it in several other projects at ASU. However, the adoption of my research products in the day-to-day operations of agencies and stakeholders has rarely happened. I hope the center will help achieve this extra step.”

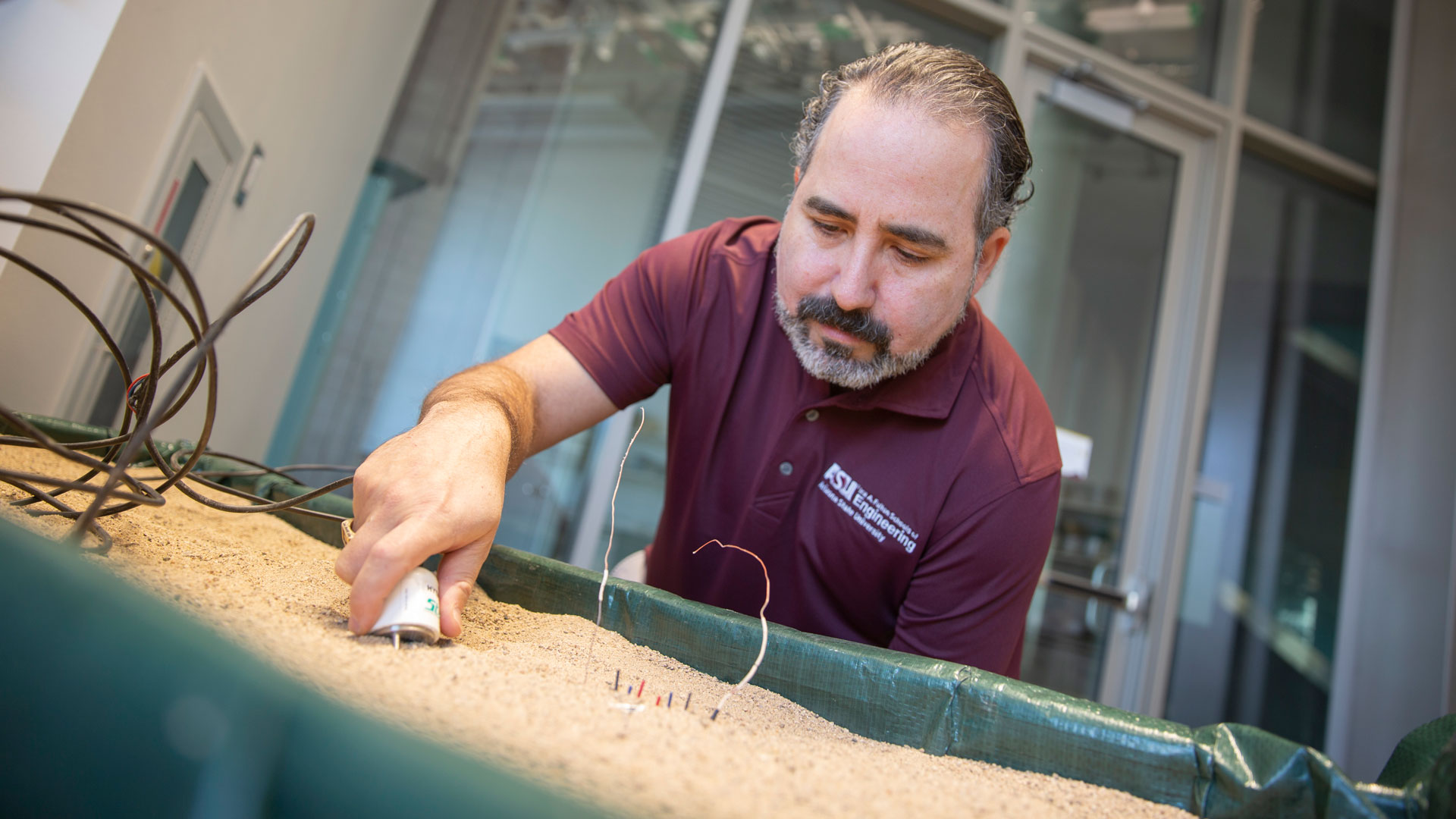

Associate Professor Giuseppe Mascaro (left) and Fulton Professor of Hydrosystems Engineering Enrique Vivoni have collaborated on the creation of a first-of-its-kind hydrologic modeling system that uses satellite data and mathematical concepts to increase the spatial resolution of soil moisture information. Vivoni wants to expand the reach of the hydrosystems engineering faculty’s research through the Center for Hydrologic Innovations. Photographer: Erika Gronek/ASU

Arizona economic impact

The goal of the solution spaces is to develop new software tools, algorithms and visualization approaches that support improved monitoring, forecasting and understanding of hydrologic systems. These innovations are often generalizable beyond a specific project for a particular client or partner.

Vivoni sees opportunities for the center to promote a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship among the faculty researchers. In line with ASU’s strength in securing patents, the center’s research team plans to apply for patents and eventual licensing in coordination with Skysong Innovations, which helps to translate research by ASU and its partners into real-world impact.

Vivoni and Zhaocheng Wang, a graduate research assistant affiliated with the center, have already obtained a provisional patent for a method to detect water presence in arid rivers through Earth-observing systems. The robust algorithm underlying the method can be used to detect water changes in other environments as well, such as agricultural areas, coastal zones, forests and the built environment.

“We have the ability to take university innovation into the marketplace within the water resources sector and be used by a wide range of professionals in a shorter amount of time,” Vivoni says.

He notes that recent advances in cloud computing, remote sensing, computing power and other technology developments have allowed hydrosystems engineering innovations to be scalable for use outside of academia for the first time.

“The timing is good now because it’s a lot easier to go from university research to implementation in the real world at a massive scale,” Vivoni says. “Few university researchers have figured out how to do this yet.”

In addition to the center’s solution space partners, Vivoni says there is another emerging market for their work.

“There’s an entire industry of climate and water startups engaged in advancing environmental data, decision-making data and IT,” he says. “We can get what we do out there more quickly and impact certain areas that are ready to absorb these advances as they’re created.”

The Phoenix area and the entire Western U.S. have a large number of professionals in water-related careers who can also benefit through workforce development training. Vivoni plans to host workshops and other training events where these professionals can learn how to use the tools and techniques developed through the center.

The center’s approach is a flexible model that he says is reproducible for a wide range of stakeholders, projects and problem spaces.

“I can imagine that if we’re successful, there’s going to be center directors in probably every state that come to us to learn how we implement our solutions spaces, partnership and market adoption models,” Vivoni says.

But first, their focus is closer to home.

“While our work is global in impact, we begin with local partners in Arizona and the Western U.S. where water is a vital resource for society.”